Hap Bagget assembles a a group of partners bent on changing the face of southeast Fort Worth.

Some boys never get over playing in the dirt. Happy Baggett is one. It’s just that the amount of dirt he’s playing with these days is measured in acres. Lots of acres. He’s the driving force behind Renaissance Square, a massive development at Berry Street and U.S. Highway 287 that is bringing shopping, health care and housing to one of the most undeserved and poorest areas of Fort Worth.

It started as a business deal, and while it is still that, it has morphed into a project bringing together many different interests in Fort Worth, in Texas and from across the country that is remaking the face and fabric of Southeast Fort Worth.

Investors Mark and Shauna Trieb were vacationing in Italy in 2006 when they decided to participate in the deal without ever seeing the land. They initially expected to hold the land for perhaps three years and make a killing on the investment. “That’s what our intention was,” Mark Trieb said. “Our intention changed. Our intention now is to create a sort of a master planned community in the inner city of Southeast Fort Worth that will bring together families and kids in an environment that is supported by a number of diff rent healthy attributes, and cradle-to-college education.”

For as long as most people can remember, folks in the area had to go elsewhere to shop for virtually anything, especially fresh produce that wasn’t available at countless convenience stores. Many had no transportation other than buses. Now Southeast Fort Worth is home to Tarrant County’s largest Walmart, on 19 acres of what once was the Masonic Home and School of Texas, which operated on 206 acres from June 1899 to May 2005.

It was the largest undeveloped piece of land in Fort Worth inside Loop 820, and big tracts are rare in the inner city. The Mallick Group Inc., a Fort Worth-based real estate and energy-related investment firm, bought the land in 2006. Baggett puts deals together, and mutual friends connected him with Michael Mallick. Then, says Mallick, it was “luck and fate.”

Mallick had worked to free up developable land on the site that had been encumbered by natural gas leases, and he was having dinner with a potential investor group after a day of touring Southeast Fort Worth when Baggett walked by the table and asked what deal he was working on. So Mallick told him.

“Hap is that way, something I like about him,” said Mallick. “Hap leaned down and told me that he wanted to buy the property right away. I didn’t think much of that exchange until the next morning when Hap showed up at my office wanting to work out a purchase and sale agreement.”

Baggett is a horizontal developer. He works with the dirt and finds other people to do the vertical development. One developer backed out in 2008 when the economy went south, but Lockard, a major developer based in Cedar Falls, Iowa, stepped in and Moriah Real Estate Co., out of Midland, joined as a capital partner. Baggett, who is from Odessa, says he’s been doing deals with Moriah for 20 years.

Others might not have been so bold, given the economy at the time. But John Flint, executive vice president of asset management for Lockard, says Moriah’s involvement was one of two key factors in the decision. “To be perfectly honest, they were just as excited about the overall economic impact for that entire part of the city as they were the financial impact that investment would have for them,” he said. “Patient capital,” he called it.

The second factor was the financial commitment from the City of Fort Worth. “They understood that this would be a difficult area of town to develop in. It had not been happening for decades. They knew they were going to have to step up and provide a financial assistance for the project in order for it to move forward,” he said. “It’s a great project in a part of town that’s been long overlooked, and we’re really proud of it and appreciate other folks feeling the same about it.”

The project also caught the attention of Purpose Built Communities, an Atlanta-based nonprofit consulting group that works with local leaders to plan and implement holistic revitalization efforts. Baggett notes that Purpose Built is not a developer, but it is a resource for a planned Renaissance Heights United Foundation and the holistic development concept. The project is now a network member of Purpose Built.

The dream is to radically change Southeast Fort Worth. “It already has,” said Carl Pointer, a resident of the nearby Rolling Hills neighborhood and a leader in a neighborhood alliance called United Communities Association of South Fort Worth.

The seven census tracts that immediately surround Renaissance Heights give a picture of the issues that have faced parts of Southeast Fort Worth for decades. The median household income in the area is $27,707; that’s 54 percent of Fort Worth’s median income of $51,105. Five percent of residents in the area have college, advanced or professional degrees compared with 26 percent of Fort Worth as a whole.

But the draw area for the shopping at Renaissance Square is much larger than those seven census tracts, and a 2008 study by Social Compact Inc. commissioned by the City of Fort Worth showed a larger marketplace than was previously known. Called the Southeast Fort Worth Neighborhood Market Drill Down, the study found aggregate household income of about $2.5 billion — $516 million more than the conventional market estimate of roughly $2 billion. “That was a very important part of the deal,” Baggett said.

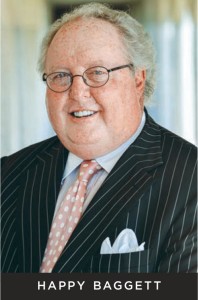

DOGS AND FLEAS

Baggett is known all over Texas for his mission statement. “ ‘Find the big dog, lay down next to it, and let the fleas jump on you.’ That’s how I do deals,” he said. It has worked well for him over four decades of doing deals in Dallas, Roanoke, Trophy Club and the Alliance area. “My joke with Hillwood was they’re elephant killers. I kill lions, tigers and bears,” he said.

He might have been a Broadway musical comedy star. In the 1960s Odessa High School was to music what Odessa Permian was to football, and Baggett was offered a scholarship to study music at what was then West Texas State in Canyon. “I would never have imagined his interest in real estate back in high school in the late 1960s,” said high school classmate and longtime friend Aubin Petersen.

“Happy was active in junior high and high school a cappella choirs and ensembles,” she said. He was highly respected in high school, was repeatedly voted runner-up for Most Dependable, and was Class Favorite runner-up his senior year. “Happy was always my go-to friend when I needed advice, a ride, a friend or just someone to hang out with.”

“Happy was active in junior high and high school a cappella choirs and ensembles,” she said. He was highly respected in high school, was repeatedly voted runner-up for Most Dependable, and was Class Favorite runner-up his senior year. “Happy was always my go-to friend when I needed advice, a ride, a friend or just someone to hang out with.”

Classmates included Larry Rudy and Steve Gatlin of the Gatlin Brothers. But Baggett gave up his music career when he got married and started a family. He attended Odessa Junior College briefly before his father-in-law offered him $200 a week to work for him. He didn’t quit singing, but performed only as an amateur in local productions.

“We did everything — industrial, retail, office, residential. That’s where I got my start in real estate,” Baggett said. “I started out digging footings with shovels, putting in rebar, pouring the concrete. My father-in-law’s concept was if you don’t know how to do the job, you can’t bid, you can’t watch it, you don’t know what to expect from people who are working for you.”

He also learned that it wasn’t construction that interested him. It was finding and acquiring the land that intrigued him. He moved to Dallas and through church connections and other relationships worked for and became partners with some of the biggest developers in North Texas. “What I’ve done since ’96 is raise capital with investor partners. I put the deals together and go to investor partners who come help me develop the site,” he said.

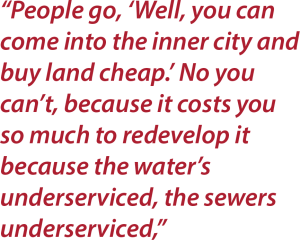

Happy Baggett has a well- developed sense of humor, but he’s always serious about business. He mostly worked in green fields — open land waiting for development — and that’s a different beast than inner city development. “People go, ‘Well, you can come into the inner city and buy land cheap.’ No you can’t, because it costs you so much to redevelop it because the water’s underserviced, the sewers underserviced,” he said. “It’s probably twice and maybe three times as expensive to develop in the inner city as it is to go out to Alliance and buy a raw piece of dirt.”

BUILDING TRUST

The chance to buy the old Masonic Home property came in 2006, when there already were unfavorable economic signs on the horizon. “Things were starting to turn down a little bit. I‘d been looking and seeing things slowing down in the green fields I was developing. I was always out in front. So now I’m way behind,” he said. “So I made this 180 degree turn, it was the largest undeveloped tract of land inside the Loop in Tarrant County, so to find raw land like that is just, ‘Wow.’”

Happy Baggett freely admits that he didn’t quite know what he was getting himself into. What he saw was a big piece of dirt with a lot of possibilities. The rest — the social impact part — came later. “I didn’t even know how much was going on in the community and the need here, but when you’ve done this for 45 years, you go, ‘That’s a deal. Let’s go get it,’ ” he said. Integral to making the project a success was gaining the support of neighborhoods weary of unfulfilled promises and developers who residents thought were simply trying to milk the neighborhoods.

Mallick had given him a head start on that. “Around 2002 or so, Michael Mallick talked to a group of us about buying the Masonic Home and about rezoning and about his plans to redevelop it and have a commercial corridor,” said Pointer.

Mallick was developing a residential community about a mile away called Sierra Vista. “We all just hit it off. He understood what our concerns were. He explained his concerns. It was a meeting of the minds — it was kind of the Vulcan mind merge,” Pointer said.

Mallick asked what the neighborhood wanted. And the group told him what they didn’t want. “We don’t want pawnshops. We don’t want tattoo parlors. We don’t want any more liquor stores. We don’t want places selling fortified liquor,” Pointer said. But they did want a Walmart.

They had raised money and placed a full-page ad in the Benton, Ark., newspaper — where Walmart is headquartered — urging the company to come to Southeast Fort Worth. They collected sig natures and

natures and

letters and mailed them to every member of the Walmart board of directors. Then “Michael got with Hap and that’s when things got rolling,” Pointer said.

Even before the deal closed, Mallick urged Baggett to go to a meeting of United Communities “There was a little 83-year-old lady who rolled up in a wheelchair and she said tell me what you want to do. I said I’m going to go through the presentation. She said, ‘Mr. Happy’ — I’m Mr. Happy in Southeast Fort Worth — ‘we need a grocery store. It’s over 20 miles roundtrip for me to get fresh vegetables and I’ve got diabetes,’ ” Baggett said. Infant mortality in the primary ZIP codes— 76105, 76112, 76119 and 76120 — is consistently among the highest in Tarrant County. Household income is low. “So the need part just started coming in,” he said.

Community trust was important for a number of reasons, not the least of which was to avoid challenges to proposed zoning changes necessary to make the housing component of the project work in a later phase. “When you’ve been in an area of town … that feels it has been lied to for 30 years by community leaders — we’re going to do this, we’re going to do that — and nothing has happened, you’ve got to build trust,” Baggett said.

“There’s still an element of that here,” said Pointer. Baggett took that to heart, and in the just over three years before breaking ground on the Walmart, his logbook shows 671 entries — large group meetings, small group meetings, one-on- ones, phone calls with community leaders in the area and other related calls. The Walmart opened in the first quarter of 2013.

THE NON-PROFIT COMPONENT

The retail and housing aspect of the project is easy for even a layperson to understand, but Renaissance Square is much more complex than that. There also is a nonprofit and institutional aspect to it.

At one point, Mallick owned more than 300 acres in the area, something most developers at the time would have considered risky. That included more than 100 acres at East Berry Street and South Riverside Drive that became the Sierra Vista housing development. New housing is a big deal for Southeast Fort Worth because home stock in the area is aging. The percentage of ownership and rental properties roughly tracks Fort Worth and Tarrant County, but in the area immediately surrounding Renaissance Square, the percentage of vacant properties is higher, and the housing is older. The median year of construction is 1957, compared with 1983 for Fort Worth and 1984 for the county.

When he struck the deal with Baggett and his investors, Mallick kept the land with the old Masonic Home buildings and went looking for a worthy charity to donate it to. He had prospered in the area, and “we wanted to have something of significance to give back to our community.” He could easily have sold the property. “We had many conventional parties who wanted to purchase the property for cash, and we turned all of them away. We had many nonprofits who solicited us, and whom we solicited, and several of them wanted the campus. Ultimately, ACH proved to be by far the most qualified and worthy recipient,” he said

ACH, formerly known as All Church Home, works with children and families to deal with abuse, neglect and family separation and to help children overcome these things when they do happen.

“The donation was a surprise,” said ACH CEO Wayne Carson. “ACH had a strategic plan that called for expanding our campus to better meet the increasing needs of children and families seeking help, but we had not started looking for options yet and had not publicly announced that we were looking to expand. The timing of the opportunity was perfect for us, but it was unexpected and a very nice surprise.”

What Carson calls the Wichita campus — the address is 3712 Wichita St. — in the long run will enable ACH to operate more efficiently. “There is adequate space to eventually allow us to move programs we currently operate on our Summit Avenue campus, which puts us in a position to sell the Summit property. This is a win-win for children and families because we will be able to offer programs on this beautiful campus,” he said.

But ACH is not the only nonprofit on the site. The YMCA is building there, and Cook Children’s Health Care System has opened a clinic on perhaps the most prominent visual location on the northwest corner of Renaissance Square. Cook actively seeks areas where children are medically underserved to open clinics. “Our research when planning our latest neighborhood clinic revealed that ZIP code 76119 was one such area, and Renaissance Square was a destination point within that ZIP code,” said Larry Tubb, senior vice president/System Planning and The Center for Children’s Health at Cook Children’s. A Dallas-based charter school, Uplift Education, bought the old Masonic Home high school and gymnasium, which was not included in the gift to ACH.

But ACH is not the only nonprofit on the site. The YMCA is building there, and Cook Children’s Health Care System has opened a clinic on perhaps the most prominent visual location on the northwest corner of Renaissance Square. Cook actively seeks areas where children are medically underserved to open clinics. “Our research when planning our latest neighborhood clinic revealed that ZIP code 76119 was one such area, and Renaissance Square was a destination point within that ZIP code,” said Larry Tubb, senior vice president/System Planning and The Center for Children’s Health at Cook Children’s. A Dallas-based charter school, Uplift Education, bought the old Masonic Home high school and gymnasium, which was not included in the gift to ACH.

Baggett said the community initially told him no charter school. “But their concept of a charter school is mine too, very small, strip center, underfunded,” he said. Uplift is different, and when he went back to the community to explain the differences, leaders agreed. The result is an 11-acre tract with an almost 200,000-square-foot school. Uplift Mighty Preparatory opened for the 2012-13 school year and has 747 students in the current school year. It is planned as a K-12th grade school, and currently teaches K-3 and 6-9.

Baggett’s partnership sold Uplift the land and made a $2 million donation. It gave the Y $600,000. That’s not completely altruistic, and like most things with Baggett it is founded in business. It keeps the appraised value of the land up, which helps in the next deal, and the partners get a tax write-off. “So at the end of the day, the nonprofits get what they need from a dollar standpoint, we get what we need from an investment standpoint,” he said. “We keep our land values up, and they get a cheaper price.”

Baggett, who has a doctors’ office building planned for the site, thinks that ultimately “we’re going to be a very strong institutional site.” He has 40 acres for such placements. “That’s a different ballgame from retail and residential, and the more you get, the more you attract.”

BRINGING RETAIL

Lockard, the vertical developer at Renaissance Square for the 67-acre shopping center, is a key component in the mix. “Even though I’m a land guy, you have to know how retailers think,” Baggett said. “I sell my land to vertical developers who have long track records, who have built Targets and Walmarts all over the country.” He had early construction experience, but says, “If it’s taller than my height, I don’t build it.” That’s a good thing, because that would be 5 feet 6 inches.

Financing on the project is complex, especially considering that the major development effort began in the worst recession since World War II. “When it does that for six years, everybody goes broke,” Baggett said. “This got car dealers, criminal defense attorneys, retailers; everybody got hit in this one. It wasn’t just oil and gas and savings and loans.” People ask how the partners did it. “We got up every day and went to work. We knew infill. We knew there were 130,000 people in that area who had money, thanks to the Social Compact Inc. survey that the city paid for. So we proved that there were higher incomes, that there were higher housing stock values in that area.”

Baggett had never done a tax increment financing agreement before Renaissance Square. “I’d never taken a dime from government on any project in my life,” he said. “I was proud of that. This one made sense to get the deal done.” But he didn’t have to ask for it. “The city came to us and said with your plans, this is what we’ll do. Of course, we get to pay for everything upfront and get paid back later. So the support we got from the city was just phenomenal.” One mark of pride is that the late Chuck Silcox, a lovable curmudgeon and city council fiscal hawk, voted for it — the only TIF he ever voted for. “It’s strictly public improvement,” Baggett said. “We don’t get to spend anything on the building. It’s strictly streets, water, sewer, fencing, demolition and those types of costs.” City of Fort Worth participation in the project is $5,650,000 in the TIF, and a $12,500,000 Sales Tax Sharing Agreement.

Baggett had never done a tax increment financing agreement before Renaissance Square. “I’d never taken a dime from government on any project in my life,” he said. “I was proud of that. This one made sense to get the deal done.” But he didn’t have to ask for it. “The city came to us and said with your plans, this is what we’ll do. Of course, we get to pay for everything upfront and get paid back later. So the support we got from the city was just phenomenal.” One mark of pride is that the late Chuck Silcox, a lovable curmudgeon and city council fiscal hawk, voted for it — the only TIF he ever voted for. “It’s strictly public improvement,” Baggett said. “We don’t get to spend anything on the building. It’s strictly streets, water, sewer, fencing, demolition and those types of costs.” City of Fort Worth participation in the project is $5,650,000 in the TIF, and a $12,500,000 Sales Tax Sharing Agreement.

Here’s how it works: “Walmart might say we need to do $50 million a year in sales, and the best number we can come up with is $35 million. The city runs the number. Everybody runs the number. There’s a gap here. How do we fill the gap until the market catches up?” Baggett said. That’s where the TIF and tax sharing come into play on inner city developments — filling that early gap.

And there is an additional lure for big national companies. When companies like Walmart and Marshall’s want to raise money from investors like CalPERS and other pension funds, the potential investors ask what the companies are doing in inner city America. They get beat up all the time, and deals like Renaissance Square look good on their proposals. “So when you find one that works, that’s a gold star on your forehead,” Baggett said. Walmart owns its land and built its own building. The shopping center developer makes money by building suites and leasing to junior tenants and leasing or selling pad sites to other companies. “I pick the vertical developer,” Baggett said. “I set all the planned development guidelines, set-back, architecture. I do all of that. I don’t just sell a raw piece of dirt and say go do what you want with it.”

The Shoppes at Renaissance Square held its Grand Opening on Nov. 6, 2013.

BUILDING HOUSING

With the retail development underway, the attention turned to housing. Baggett and his partners had laid the groundwork with the community so that when they asked for zoning changes to allow multifamily housing on the more than 100 acres that had been zoned for 5,000-square-foot lots, there would be no opposition.

He needed multifamily housing because he needed the population density nearby, but community leaders were skeptical about apartments. “The community had this reputation of being opposed to development and was difficult to work with,” Pointer said. “For some many years, people wanted to put really cheap, exploitative type of businesses in. Cheap apartments that over four or five years would turn into some really bad places. That’s what people were afraid of.”

some many years, people wanted to put really cheap, exploitative type of businesses in. Cheap apartments that over four or five years would turn into some really bad places. That’s what people were afraid of.”

But the crumbling apartment complexes residents drove past daily were far from what Baggett and others had in mind. “We had a couple of people make offers to buy some land to build some apartments, but we just weren’t comfortable with them and weren’t comfortable with the quality of the apartments they were going to build,” said investor Trieb. “We didn’t really have our master plan in mind for what we were going to do, so we turned them down to kind of tread water for a while.”

Then one day the Treibs were listening to The Time Of Our Lives: A Conversation About America by Tom Brokaw in their car during a trip. Brokaw talked of the successful revitalization of the East Lake Meadows community in Atlanta by real estate developer and philanthropist Tom Cousins. It was a devastated area of Atlanta with some of the worst crime rates in the country, marked by drug use, substandard schools and extreme poverty.

They just looked at each other, they said. “We didn’t know ahead of time that was what we were looking to do, but once we heard the story of somebody else having done it, we knew that was what we wanted to do,” said Shauna Trieb.

The Atlanta effort began in 1995, and in 2009 it led to the establishment of Purpose Built Communities to help other communities deal with similar blighted areas. Under the Purpose Built plan, communities replace low-income housing with mixed income housing, establish a “cradle to-college” education pipeline and bring in wellness and support services. That’s followed by retail and job creation. Fort Worth did it in reverse, with retail first.

Purpose Built has helped set up an organization called Renaissance Heights United to coordinate the delivery and availability of services in the area. Tubb, of Cook Children’s, chairs the working group. Plans are underway to form a nonprofit called Renaissance Heights Development Group.

Columbia Residential of Atlanta is developing the apartments, and Baggett said they will be mixed-income – voucher, rental assistance and market rate, with about a third in each category. “The best way to help break the cycle of poverty is stop concentrating poverty,” Baggett said. “Provide Class A housing stock that will attract market-rate tenants and put voucher tenants in a development that they would never hope to live in. Seeing a way out is the greatest hope you can give someone.” Baggett said 27 acres of the site are dedicated to apartments at 18 units per acre. Plans include about four acres of senior housing, about 14 acres of townhomes and 19 acres for single-family housing.

An interesting statistic about Southeast Fort Worth is that the population in the area increases about 15 percent on Sundays, Baggett said, and he interprets that as people who grew up there and live somewhere else returning for church. They’d move back if they could find acceptable housing. They don’t want to refurbish a 50-year-old house. They want 10- foot ceilings, eight-foot doors, a clubhouse, a workout room and a resort-level swimming pool, Baggett said, and that is what the developer is going to build.

“I talked with a lot of young professionals when we talked about spending the minimum of around $100,000 per unit with all of the amenities you’d have in any other really nice multifamily community in the Metroplex,” Pointer said. “A lot of the younger folk were excited. But they want to get the best bang for their buck like everybody else.”

COOPERATION

No matter whom you talk to, those involved in the development stress the collaborative effort it takes to redevelop the area.

“All projects within the 300- plus acres my company assembled, entitled, purchased, developed and/ or sold were only possible because of a true collaborative partnership with the neighbors who live within several Southeast Fort Worth neighborhoods, countless city staff members, thousands of hours of planning and the investors who backed developers like Hap,” said Mallick.

Lockard’s Flint noted that the city’s commitment extended far beyond financial. “The City of Fort Worth has been phenomenal to deal with from the economic development folks all the way through engineering and permitting and inspections,” he said. “All those folks have been really just a class act to deal with, and we really appreciate them.”

The Treibs are from Dallas and praise the efforts of all involved in the project, and not just for a meeting here and there. “They keep going at this harder and harder, meeting after meeting, month after month, people taking on board positions and community positions, and reaching out to their friends and raising money. Not that we have any experience to say that someplace else couldn’t do it, but it’s been very impressive what people have come together to do,” said Shauna Trieb. Husband Mark agreed. “The camaraderie that Fort Worth has and those leaders have together is pretty amazing for us to witness, and we’re happy to be a part of it. We feel very fortunate to be in the position we are in now.”

Perhaps he summed up the vision and dream for all involved. “We look forward to coming back in 10 years and walking the neighborhood and seeing little kids playing in ·the park, and people smiling and talking to each other – a neighborhood like any middleclass, upper-class neighborhood, but in Southeast Fort Worth. We’re looking forward to that. And working toward it.”

And it all happened in what people like to call the Fort Worth Way.